Cuneiform at the Pergammon

At the Pergammon Museum, I veered away from the great blue facade of the Ishtar Gate (shipped brick-by-brick from the Middle East many decades back in wooden crates, one of which sits on a pedestal in the hall, still stamped with the shipping labels) and into the side rooms that house glass cases of cuneiform tablets.

While I’ve learned to question my reflexive desire to drill down on the origins of things, especially Western cultural things, it’s not a mystery why I would want to do so with writing. Writing is a kind of magic, and like any magician I want to learn the spell.

And so, I go in and I look at the tablets.

What would become cuneiform writing arose thousands of years ago in the ancient river cities of what is today Iraq. it did not come about to make one’s inner thoughts or feelings understood, but seemed to have got its start from administrative lists. Record-keeping. As a reformed bullet-journaller, I recognize the urge that drove those first scribes to move the endless reams of data from your head into some external form and free up some mental space.

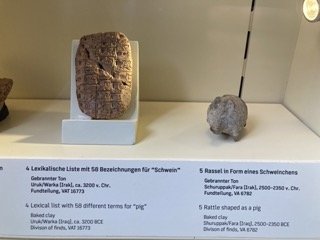

One way they did this, around the second half of the fourth century BCE, was with hollow clay bullae - ball - full of tokens - a kind of ersatz piggy bank of data. The tokens were inscribed.

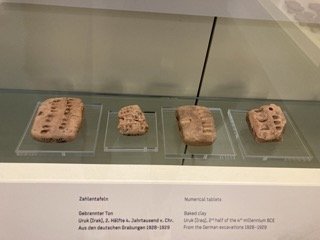

Apparently it became easier at some point just to make a list. So administrators listed signs or stylized pictures of thing thing being tallied.

And then the list tilted 90 degrees, and instead of a list, it was a line.

(Disclaimer: To be clear, I am not an Assyriologist. And I am not at all sure that these exact tablets represent the stages I’m describing - they likely don’t. I was just fascinated that they had some examples of these intermediate forms.)

And then, instead of recording sheep or wages, a sign became not just a picture of the thing it signified, but a logogram that could be pulled into service as a vowel, a syllable, a symbol, a line. A fact.

A king. A construction project. An inscription.

And writing.

I think the significance is really hard to overstate. Language is one of the hallmarks of what we might term culture, and not in the red velvet caviar opera sense. Writing both solved the problems of survival, and opened up unimaginable new ways to thrive. And I think it happened because we’d become urban, we’d built the first cities and all the mad rush of interaction that entailed, and we had so much information to keep track of, and we could now do it without needing to remember every single thing. I am still thinking about this. I am still wondering what written language means for a mind. What is my mind without words? What is a word to me without a knowledge of what it looks like written down?